On Mikhail Romm's 'Ordinary Fascism' (1965)

Romm carries a responsible synthesis of politics and art, not betraying either but rather focusing on the goal of educating and elevating the intellectual and political capacity of the viewer.

This essay is distilled from remarks made at the first postamerican.ist film screening, featuring Mikhail Romm’s ‘Ordinary Fascism’ in March 2025.

Most of us have ingested the typical assumptions of fascism. Relegated to the 20th century, dressed in Hugo Boss jackboots, goose-stepping in black and white under the shadow of so-called totalitarian antagonists. In popular memory, fascism is something extraordinary. There is a disinterest in the quotidian and mundane reproduction of fascism—the daily work of maintaining a dystopia. As such, there’s a certain disinterest in American politics in acknowledging a returning threat—so much so that we must constantly reinvent terms and convolutions to remain discursively relevant: Neo-liberal. Neo-nazi. Alt-Right. New Right.

This novelty makes it so that the ordinariness of fascism—which is quite familiar throughout U.S. history in which many have lived ordinary lives and died ordinary deaths alongside genocide, apartheid, and imperialist war—can be made extraordinary. This is not to say there is no theoretical or historical distinction to be made among these contemporary trends or historical epochs, but that the work of repackaging an ideological product as novel despite the fact that they are not new should be a task of little interest to those seeking the construction of a new society.

Treating each conjunctural articulation of our class enemies’ strategies like a new commodity to be sold in a competitive market of ideas is the default and understandable response of many to break through the ceiling where virality is the metric for mass consciousness. Simultaneously, fascism and the pinning down of it has become a form of ideological target practice, some that take aim on it either spray their target wildly, scattershot; others take aim squarely for the head or heart or hands of the fascist target, mistaking that for the whole—either way, we find ourselves stuck at the range, while our enemies have already declared war.

We can, and should, understand the intricacies of various historical articulations of fascism—this is a question of immense concern to postamerican.ist. We should also understand what is universal about the phenomena we call fascism, but as militants, as revolutionaries, as artists or cultural workers seeking a communist horizon, we interpret the world in order to change it. We seek to sublimate reality—to accept that while we cannot abolish our links to the past we are not predestined to repeat it. We activate ourselves in the hopes others will also become activated.

So as we are confronted with the present and most recent decay of capital’s hold on society, our role becomes more than simple agitation, but charting and demonstrating that there is a path forward. Not just identifying patterns in society, but rupturing the cycle of capital’s attempts at self-preservation. The world we want—the world we need—has been conceived many times and stillborn just as many. As Soviet filmmaker Mikhail Romm repeats, “another Germany once existed.” For us in the 21st century, this is true twice over. A dozen times. More.

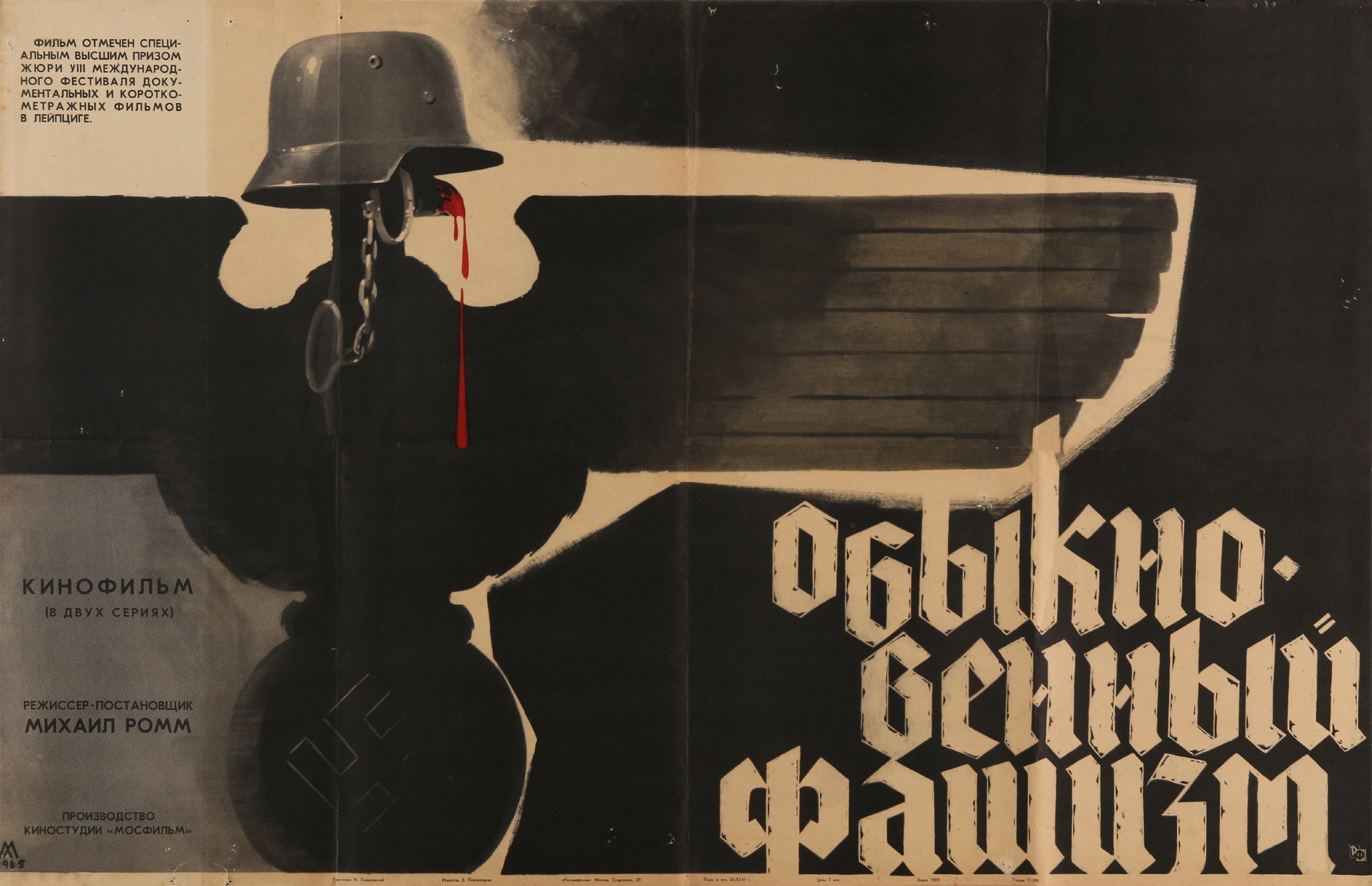

Ordinary Fascism (Обыкновенный фашизм), directed by Romm in 1965, may not resolve these assumptions of optics. The film masterfully collages found footage and archival documents from newsreels and Nazi propaganda liberated by the Red Army as they liberated the people chained under the domination of Hitler and his collaborators, those who fought and died in the tens of millions knowing that there would be a world in which fascism was defeated forever.

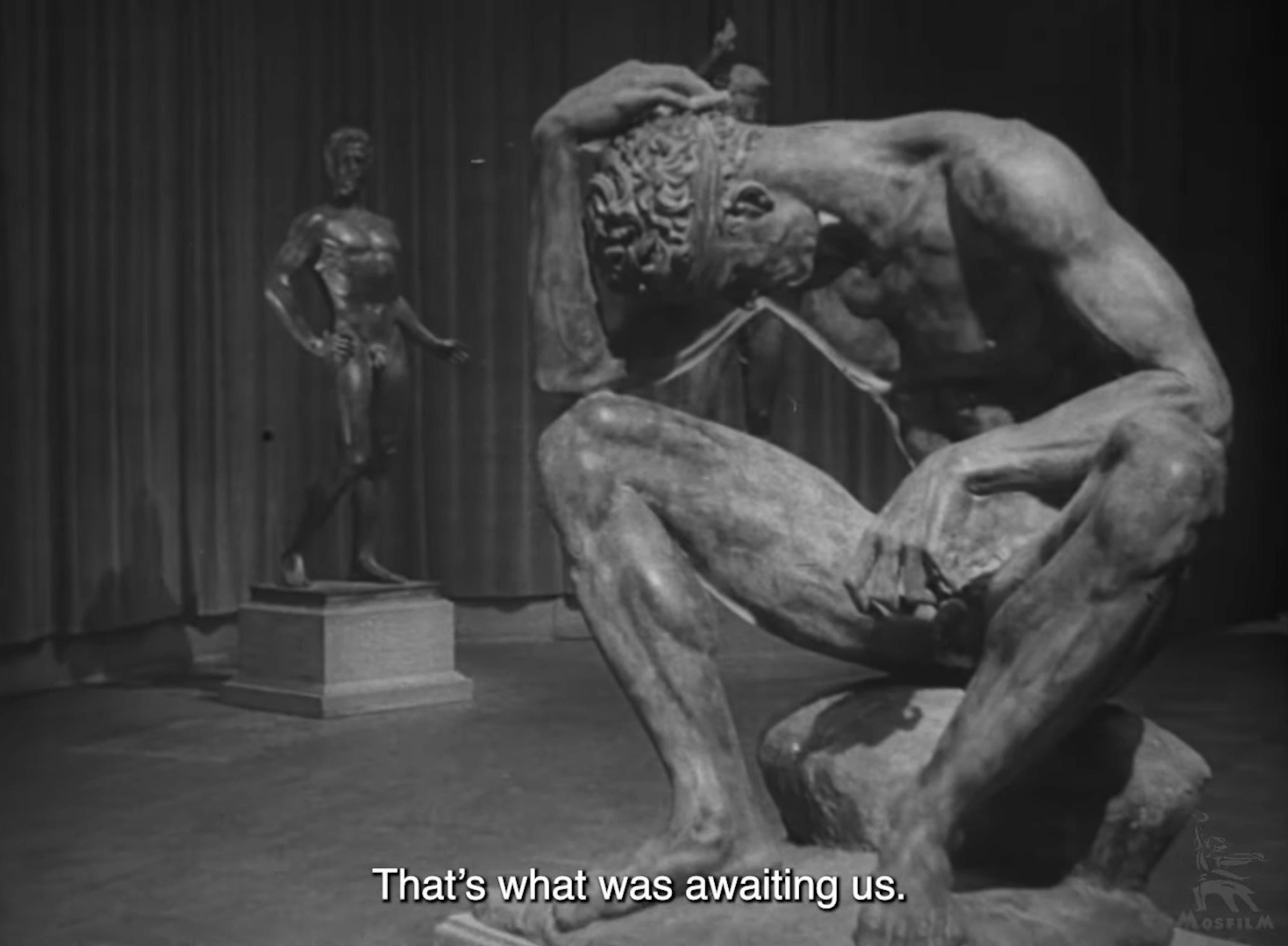

But what Romm offers in his seminal work is a class-conscious understanding of fascism. What it does resolve regarding these assumptions is determining who is on what side of the barricade between fascism and socialism. Largely free of theoretical understandings of fascism and the pop-history that a North American population is fed, it reveals the sentiment and instincts of humanity in a popular language.

Ordinary Fascism carries a responsible synthesis of politics and art, not betraying either but rather focusing on the goal of educating and elevating the intellectual and political capacity of the viewer. Human nature, as we’re told by the established powers, is competitive and cruel and individualistic. But this myth is snuffed out by Romm’s documentary, which takes necessary detours of observing the crowds of Moscow and Warsaw, observing the shared humanity of prehistoric art, showing collective living, self-reflection, and a desire to adapt and progress is the true essence of human nature. It is fascism and its capitalist roots that is the historic exception and departure from human experience.

Romm was born to a family of Jewish social democrats, who were driven to exile early in his life due to their political activity. In 1918 joined the Red Army during the Russian Civil War, and upon the defeat of the White Army and Imperialist intervenors, Romm turned to the arts. In 1925 he graduated as a sculptor from the Highest Artistic-Technical Institute, then began his career at the beginning of the 1930s in cinema, working at Mosfilm as an assistant and then a screen writer. Receiving the award of People's Artist of the USSR in 1950, Ordinary Fascism is considered his magnum opus.

So as we experience this film, wince and cry at the brutality and violence of fascism’s captivity of the masses, we do so in the study of embracing an antifascist position in our work. Not simply to self-reflect but always to bring ourselves back to reality, to human nature, which is revolution.

The film can be found here: